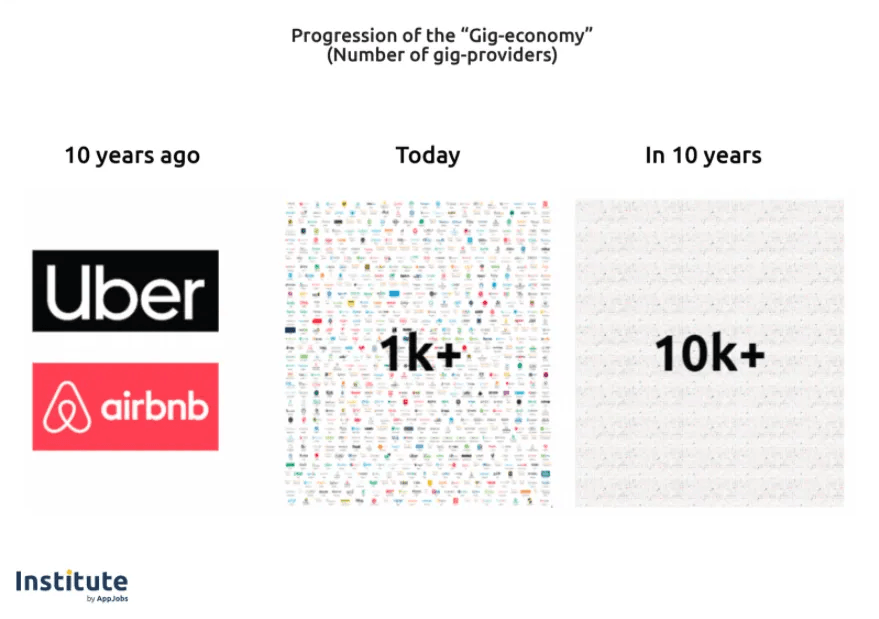

“Developments in the gig economy” is a blog series, that gives you a snapshot of how far the gig economy has come. The series will consist of three blog posts and down below is the first one, “Gig Economy Growing Pains”. The remaining two blog posts will discuss regulations and growth within the gig economy.

Gig Economy Growing Pains

The recipe to create the modern “gig economy” is fairly straightforward. Take one medium to large unemployment rate, and mix with high speed internet and smartphones. Add to that a dash of entrepreneurial culture. Let rise.

This mixture, developed in the United States, but replicated around the world, has led to an exponential growth in contract and freelance work. Powered by online platforms that connect workers to various consumers, the gig economy is projected to surpass $455 billion in value by 2023.

That growth, however, is not without its unique set of growing pains.

Federal governments around the world are grappling with the unique worker statuses that these platforms create. On one hand, the companies claim they are merely a marketplace that connects contractors to short-term work, hired by end users of the platforms. As such, they are independent contractors, which allows said companies to avoid payroll taxes, welfare system contributions and other requirements of maintaining a workforce.

Workers, on the other hand, claim that companies are taking advantage of them by refusing to provide benefits, restricting their work capacity depending on end user ratings, inappropriately booting workers from platforms and other claims. These workers are seeking greater recognition as employees of the platforms, granting them normal employee labor rights.

It has been left up to the federal courts to sort out the labor rights of gig economy workers. And much like any matter this complex, it varies from country to country.

In France, the Cour de Cassation, the nation’s top court, has recently ruled that Uber drivers should be classified as employee rather than a contractor. The court made the decision based on the fact that drivers could not set their own prices or build their own clientele independently. As such, the court said workers were subordinate to the platform – and are employees as a result.

Beyond the daunting challenge this poses to Uber’s business model, it will likely require Uber to contribute to France’s state welfare system through various taxes – a potentially significant expense that Uber has conveniently avoided to date.

The ruling follows a similar decision against the food delivery app Deliveroo in 2019. In that case, the firm was ordered to pay a delivery cyclist €30,000 for refusing to hire the cyclist as a full-time employee.

In an effort to address the emergence of these gig platforms and the unique questions they pose to the workforce, the European Parliament has issued a series of rules to improve transparency between platforms and workers. The EU law will require all employers to issue the following information on an employee’s first day of employment (be it temporary or full time):

– Starting date

– Pay information

– Define a standard workday or reference hours

– Description of duties

– Compensation rights for late cancelling of work

Employers will also be prohibited from using exclusivity clauses that prevent workers from having other jobs, and may only utilize one probationary period for new workers with a maximum of six months.

Federal regulations and scrutiny aren’t limited to Europe, though. In Australia in 2018, the Fair Work Ombudsman brought a legal case against another food delivery service: Foodora. The ombudsman alleged that the company was engaging in fraudulent contracting, which caused underpayment of three workers. The claims revolved around the question of whether the workers are independent contractors or full-time employees.

While that case appears to be mirroring the French rulings, Australia’s federal government has ruled in favor of other gig platforms including Uber. The Fair Work Commission has confirmed that, in Uber’s case, drivers are not recognized as employees. The reason being was that the platform does not create a “work-wages agreement” between Uber and its drivers. Essentially, there is not a contract to perform work, nor a contract to pay for that work.

After laying out criteria by which the government defines an employee, currently, Australia’s gig economy workers are classified as independent contractors. As such, they don’t have the same benefits as employees.

Halfway around the world, Brazil’s São Paulo employment tribunal has also issued fresh rulings in favor of firms. The cases involved food delivery firm iFood and logistics company Rapiddo. At issue was a similar question over whether workers are independent contractors or if they are employees, and as such, are entitled to certain benefits.

What these cases illustrate is that there is a fundamental question of what rights workers in the gig economy should expect. What unemployment benefits are afforded? How can workers and firms settle compensation disputes? How much freedom and responsibility are workers afforded? Are companies expected to contribute payroll taxes and to state welfare programs? And crucially, how can gig economy firms maintain their existence and grow within regulation?